January Market update - A rollercoaster year ends on a high note

In terms of finance, as in so many ways, 2020 was a year none of us will ever forget. The initial outbreak of Covid and fears about its rapid spread sent stocks and Treasury bond yields plummeting in March. The broad-based S&P 500 Index lost nearly 33.9% within a month’s time (Yahoo Finance S&P 500 data). The downdraft was fueled by the massive amount of uncertainty that surrounded the lockdowns and unprecedented interruption of economic activity at home and abroad.

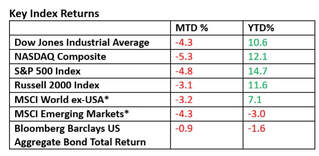

Key Index Returns:

Key Index Returns:

Source: Wall Street Journal, MSCI.com, MarketWatch, Morningstar

MTD returns: Nov 30, 2020-Dec 31, 2020

YTD returns: Dec 31, 2019- Dec 31, 2020

*in US dollars

Why we don’t endeavor to time the market

The swiftness of the decline was unexpected and unprecedented. But the recovery, which was borne out of extreme pessimism, caught many analysts by surprise. Before I briefly jump into the numbers, let me reiterate one of the themes that regularly surfaces during discussion about investments. One must be right twice to successfully time the market. You must correctly call the peak and the trough, or something close to the top and bottom. No one can do that consistently.

As the major indexes rallied from the March 23 low, many analysts continued to warn of further declines, which never materialized. These analysts are smart people. They know their craft. But to frame it in the simplest terms, even very smart people can’t predict the future with certainty. No one can. As baseball manager Yogi Berra once said, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” It’s a statement that has also been attributed to Mark Twain. That said, back to the numbers. How did the latest bear market stack up to past bear markets?

Since WWII, bear markets have lasted an average of 14 months, with a bear market defined as a 20% or greater decline in a key index such as the S&P 500. The S&P 500 has fallen an average of 33% during bear markets.

The bear market in 2020, which was the first since the 2008 financial crisis, lasted barely over one month. While the decline in the broad-based index of 500 larger U.S companies was unusually swift, the peak-to-trough sell-off was in line with past bear markets. What stemmed the sell-off?

The Federal Reserve announced massive new programs designed to cushion what was to be a significant blow to economic activity. Meanwhile, Congressional leaders put aside their differences and passed the $2 trillion CARES Act, which was far greater than the stimulus passed in 2009.

Q2’s record decline in GDP was followed by a record rebound in Q3. Coupled with record low interest rates, stocks posted some of the best gains we’ve ever experienced. Here’s one way to gauge the rally. One hundred trading days after bottoming on March 23, the S&P 500 Index and the better known Dow Jones Industrial Average recorded their best 100-day advances since 1933.

Yet, the economy is not back to pre-Covid levels. Sure, some sectors have performed admirably, but GDP and employment remain below prior peaks. The unemployment rate is well above its early 2020 low, and layoffs continue at elevated levels. Moreover, industries that depend on person-to-person interactions such as travel, airlines, restaurants, movies and more continue to face obstacles.

The new vaccines promise to alleviate these health and economic concerns, but through 2020 year-end, and so far this year, the rollout was underwhelming. Maybe we’re just seeing hiccups as states grapple with a massive undertaking, but the year-end rally was due, in large part, to optimism that the vaccines will be widely available by mid-2021.

Making the case for stocks

As I’ve emphasized in prior conversations, stocks have a long-term upward bias, and that upward bias is incorporated into your financial plan. But stocks don’t rise in a straight line. Since 1980, the average annual intra-year pullback in the S&P 500 has been 14.2%; yet, the S&P 500 has averaged a 13% advance each year, including dividends. Last year’s pullback was 33.9%, as already stated, while last year’s total return for the S&P 500 Index, including dividends, was 18.4%. Here are some additional data points. From 1980 to 2020 (41 years), there have been:

The only time we’ve had back-to-back declines during the 41-year period was during 2000-2002 (stock bubble bursting). Additionally,

What this tells us is that a diversified portfolio of stocks has a place in most of the financial plans we recommend.

We may recommend a larger or smaller allocation of stocks based on many different variables. But in most cases, equities are an integral component of a portfolio.

I hope you’ve found this review to be educational and helpful. Let me once again emphasize that it is my job to assist you. If you have any questions or would like to discuss any matters, please feel free to give me or any of my team members a call. As always, I’m honored and humbled that you have given me the opportunity to serve as your financial advisor, and I want to wish you a happy and prosperous New Year!

MTD returns: Nov 30, 2020-Dec 31, 2020

YTD returns: Dec 31, 2019- Dec 31, 2020

*in US dollars

Why we don’t endeavor to time the market

The swiftness of the decline was unexpected and unprecedented. But the recovery, which was borne out of extreme pessimism, caught many analysts by surprise. Before I briefly jump into the numbers, let me reiterate one of the themes that regularly surfaces during discussion about investments. One must be right twice to successfully time the market. You must correctly call the peak and the trough, or something close to the top and bottom. No one can do that consistently.

As the major indexes rallied from the March 23 low, many analysts continued to warn of further declines, which never materialized. These analysts are smart people. They know their craft. But to frame it in the simplest terms, even very smart people can’t predict the future with certainty. No one can. As baseball manager Yogi Berra once said, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” It’s a statement that has also been attributed to Mark Twain. That said, back to the numbers. How did the latest bear market stack up to past bear markets?

Since WWII, bear markets have lasted an average of 14 months, with a bear market defined as a 20% or greater decline in a key index such as the S&P 500. The S&P 500 has fallen an average of 33% during bear markets.

The bear market in 2020, which was the first since the 2008 financial crisis, lasted barely over one month. While the decline in the broad-based index of 500 larger U.S companies was unusually swift, the peak-to-trough sell-off was in line with past bear markets. What stemmed the sell-off?

The Federal Reserve announced massive new programs designed to cushion what was to be a significant blow to economic activity. Meanwhile, Congressional leaders put aside their differences and passed the $2 trillion CARES Act, which was far greater than the stimulus passed in 2009.

Q2’s record decline in GDP was followed by a record rebound in Q3. Coupled with record low interest rates, stocks posted some of the best gains we’ve ever experienced. Here’s one way to gauge the rally. One hundred trading days after bottoming on March 23, the S&P 500 Index and the better known Dow Jones Industrial Average recorded their best 100-day advances since 1933.

Yet, the economy is not back to pre-Covid levels. Sure, some sectors have performed admirably, but GDP and employment remain below prior peaks. The unemployment rate is well above its early 2020 low, and layoffs continue at elevated levels. Moreover, industries that depend on person-to-person interactions such as travel, airlines, restaurants, movies and more continue to face obstacles.

The new vaccines promise to alleviate these health and economic concerns, but through 2020 year-end, and so far this year, the rollout was underwhelming. Maybe we’re just seeing hiccups as states grapple with a massive undertaking, but the year-end rally was due, in large part, to optimism that the vaccines will be widely available by mid-2021.

Making the case for stocks

As I’ve emphasized in prior conversations, stocks have a long-term upward bias, and that upward bias is incorporated into your financial plan. But stocks don’t rise in a straight line. Since 1980, the average annual intra-year pullback in the S&P 500 has been 14.2%; yet, the S&P 500 has averaged a 13% advance each year, including dividends. Last year’s pullback was 33.9%, as already stated, while last year’s total return for the S&P 500 Index, including dividends, was 18.4%. Here are some additional data points. From 1980 to 2020 (41 years), there have been:

- 7 down years, with the average decline during a down year of -13.1%

- 34 up years, with the average increase during an up year of +18.4%

The only time we’ve had back-to-back declines during the 41-year period was during 2000-2002 (stock bubble bursting). Additionally,

- 21 out of 41 years, we’ve had pullbacks of 10% or more, or an average of one every 1.95 years.

- 6 of the 41 years saw pullbacks of 20% or more, or an average of one every 6.83 years.

What this tells us is that a diversified portfolio of stocks has a place in most of the financial plans we recommend.

We may recommend a larger or smaller allocation of stocks based on many different variables. But in most cases, equities are an integral component of a portfolio.

I hope you’ve found this review to be educational and helpful. Let me once again emphasize that it is my job to assist you. If you have any questions or would like to discuss any matters, please feel free to give me or any of my team members a call. As always, I’m honored and humbled that you have given me the opportunity to serve as your financial advisor, and I want to wish you a happy and prosperous New Year!