July Client Letter: Records Are Made to Be Broken

We’ve all heard it said: “Records are made to be broken.” We celebrate record-breaking winning streaks from our favorite teams. Conversely, we hope to avoid a long string of losses. The bull market that began in 2009 is not the best performing since WWII. That title still resides with the long-running bull market of the 1990s. But it is the longest running since WWII (St. Louis Federal Reserve, Yahoo Finance, LPL Research–as measured by the S&P 500 Index). In the same vein, the current economic expansion is poised to become the longest running expansion since WWII. For that matter, it’s about to become the longest on record.

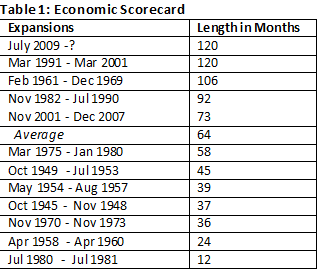

According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, which is considered the official arbiter of recessions and economic expansions, the current expansion began in July 2009. It has run exactly 10 years, or 120 months, matching the 1990s expansion–see Table 1.

According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, which is considered the official arbiter of recessions and economic expansions, the current expansion began in July 2009. It has run exactly 10 years, or 120 months, matching the 1990s expansion–see Table 1.

Source: NBER thru June 2019

Barring an unforeseen event, the current period is headed for the record books. While the economic recovery is about to enter a record-setting phase, it has been the slowest since at least WWII, according to data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve. For example, starting in the second quarter of 1996, U.S. gross domestic product, the broadest measure of economic growth, exceeded an annualized pace of 3% for 14 of 15 quarters. It exceeded 4% in nine of those quarters (St. Louis Federal Reserve).

Growth was much more robust in the 1960s, and we experienced a strong recovery from the deep 1981-82 recession. Yet, economic booms and long-running expansions can encourage risky behavior. People forget the lessons learned in prior recessions and overextend themselves. Consumers can take on too much debt. Businesses may over-invest and build out too much capacity. We saw euphoria take hold in the stock market in the late 1990s and speculation run wild in housing not too long ago.

That brings us to the silver lining of the lazy pace of today’s economic environment. Slow and steady has prevented speculative excesses from building up in much of the economy. In other words, a mistaken realization that the good times will last forever has not taken hold in today’s economic environment.

Causes of recessions

The long-running expansions of the 1960s, 1980s, and 1990s led to a mistaken belief that various policy tools could prevent a recession. Yet, expansions don’t die of old age. A downturn can be triggered by various events. So, let’s look at the most common causes and see where we stand today.

Where are we today?

Inflation is low, the Fed is signaling a possible rate cut, and credit conditions are easy as measured by various gauges of credit. For the most part, speculative excesses aren’t building to dangerous levels. While stock prices are near records, valuations remain well below levels seen in the late 1990s (I’m using the forward p/e ratio for the S&P 500 as a guide). Besides, interest rates are much lower today, which lends support to richer valuations.

Now, that’s not to say we can’t see market volatility. Stocks have a long-term upward bias, but the upward march has never been and never will be a straight line higher. As I’ve repeatedly stressed, the financial plan is designed, in part, to keep you grounded during the short periods when volatility may tempt you to make a decision based on emotions. Such reactions are rarely profitable.

A sneak peek at the rest of the year

The Conference Board’s Leading Economic Index, which has a good record of predicting (if not timing) a recession, isn’t signaling a contraction through year end. But one potential worry: a protracted trade war and its impact on the global/U.S. economy, business confidence, and business spending. Exports account for almost 14% of U.S. GDP (U.S. BEA). It’s risen over the last 20 years, but we’ve never experienced a U.S. recession caused by global weakness.

By itself, trade barriers with China are unlikely to tip the economy into a recession. Per U.S. BEA and U.S. Census data, total exports to China account for just under 1% of U.S. GDP. Even with higher tariffs, exports to China won’t grind to a halt and erase 1% of GDP. What’s difficult to model is the impact on business confidence and business spending, which in turn could slow hiring, pressuring consumer confidence and consumer spending. Simply put, there isn’t a modern historical precedent to construct a credible model. Hence, the heightened uncertainty we’ve seen among investors.

Is a recession inevitable?

It has been in the U.S., but other countries have more enviable records. Earlier in June, the Wall Street Journal highlighted, “Australia is enjoying its 28th straight year of growth. Canada, the U.K., Spain and Sweden had expansions that reached 15 years and beyond between the early 1990s and 2008. Without the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the U.S. might have, too.” If trade tensions begin to subside (a big “if”) and if the fruits of deregulation and corporate tax reform kick in, we could see economic growth well into 2020 (and with some luck, into 2021 and beyond). But, let me caution, few have accurately and consistently called economic turning points.

The Fed to the rescue

Rising major market indexes for much of the year can be traced to positive U.S.-China trade headlines (at least through early May), a pivot by the Fed, and general economic growth at home. We witnessed a modest pullback in May after trade negotiations with China hit a snag. The threat of tariffs against Mexico added to the uncertain mood until June 4th, when Fed Chief Jerome Powell signaled the Fed would consider cutting interest rates to counter any negative economic headwinds.

While Powell’s not promising to deliver any rate cuts, one key gauge from the CME Group that measures fed funds probabilities puts odds of a rate cut at the July 31st meeting at 100% (as of June 28 – probabilities subject to change). I’ll keep it simple and spare you the academic theory explaining why lower interest rates are a tailwind for equities. In a nutshell, stocks face less competition from interest-bearing assets.

But let’s add one more wrinkle–economic growth. Falling rates in 2001 and 2008 failed to stem the outflow out of stocks as economic growth faltered. And, rising rates between late 2015 and September 2018 didn’t squash the bull market. During the mid-1980s, mid-1990s, and late 1990s, rate cuts by the Fed, coupled with economic growth, fueled market gains.

It’s not a coincidence that bear markets coincide with recessions and the bulls are inspired by economic expansions. Ultimately, steady economic growth has historically been an important ingredient for stock market gains.

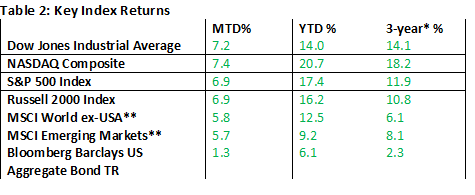

Table 2: Key Index Returns

Barring an unforeseen event, the current period is headed for the record books. While the economic recovery is about to enter a record-setting phase, it has been the slowest since at least WWII, according to data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve. For example, starting in the second quarter of 1996, U.S. gross domestic product, the broadest measure of economic growth, exceeded an annualized pace of 3% for 14 of 15 quarters. It exceeded 4% in nine of those quarters (St. Louis Federal Reserve).

Growth was much more robust in the 1960s, and we experienced a strong recovery from the deep 1981-82 recession. Yet, economic booms and long-running expansions can encourage risky behavior. People forget the lessons learned in prior recessions and overextend themselves. Consumers can take on too much debt. Businesses may over-invest and build out too much capacity. We saw euphoria take hold in the stock market in the late 1990s and speculation run wild in housing not too long ago.

That brings us to the silver lining of the lazy pace of today’s economic environment. Slow and steady has prevented speculative excesses from building up in much of the economy. In other words, a mistaken realization that the good times will last forever has not taken hold in today’s economic environment.

Causes of recessions

The long-running expansions of the 1960s, 1980s, and 1990s led to a mistaken belief that various policy tools could prevent a recession. Yet, expansions don’t die of old age. A downturn can be triggered by various events. So, let’s look at the most common causes and see where we stand today.

- Rising inflation leads to rising interest rates. In the early 1980s, the Federal Reserve pushed interest rates to historically high levels in order to snuff out inflation. The Fed’s policy prescription succeeded but led to a deep and painful recession.

- The Fed screws up. A policy mistake can be the trigger, for instance if the Fed raises interest rates too quickly and restricts business and consumer spending. This is a derivative of point number one. There were fears the Fed was headed down this road late last year. Credit markets tightened, and investors revolted until the Fed reversed course.

- A credit squeeze can snuff out growth. In 1980, the Fed temporarily implemented credit controls that briefly tipped the economy into a recession.

- Asset bubbles burst. The 2001 and 2008 recessions were preceded by speculative excesses in stocks and housing.

- Unexpected financial and economic shocks jar economic activity. The OPEC oil embargo in the 1970s exacerbated inflation and the 1974-75 recession. The tragedy of 9-11 jolted economic activity in 2001. Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait pushed oil up sharply, contributing to the 1990-91 recession. Such events don’t occur often, but their possibility should be acknowledged.

Where are we today?

Inflation is low, the Fed is signaling a possible rate cut, and credit conditions are easy as measured by various gauges of credit. For the most part, speculative excesses aren’t building to dangerous levels. While stock prices are near records, valuations remain well below levels seen in the late 1990s (I’m using the forward p/e ratio for the S&P 500 as a guide). Besides, interest rates are much lower today, which lends support to richer valuations.

Now, that’s not to say we can’t see market volatility. Stocks have a long-term upward bias, but the upward march has never been and never will be a straight line higher. As I’ve repeatedly stressed, the financial plan is designed, in part, to keep you grounded during the short periods when volatility may tempt you to make a decision based on emotions. Such reactions are rarely profitable.

A sneak peek at the rest of the year

The Conference Board’s Leading Economic Index, which has a good record of predicting (if not timing) a recession, isn’t signaling a contraction through year end. But one potential worry: a protracted trade war and its impact on the global/U.S. economy, business confidence, and business spending. Exports account for almost 14% of U.S. GDP (U.S. BEA). It’s risen over the last 20 years, but we’ve never experienced a U.S. recession caused by global weakness.

By itself, trade barriers with China are unlikely to tip the economy into a recession. Per U.S. BEA and U.S. Census data, total exports to China account for just under 1% of U.S. GDP. Even with higher tariffs, exports to China won’t grind to a halt and erase 1% of GDP. What’s difficult to model is the impact on business confidence and business spending, which in turn could slow hiring, pressuring consumer confidence and consumer spending. Simply put, there isn’t a modern historical precedent to construct a credible model. Hence, the heightened uncertainty we’ve seen among investors.

Is a recession inevitable?

It has been in the U.S., but other countries have more enviable records. Earlier in June, the Wall Street Journal highlighted, “Australia is enjoying its 28th straight year of growth. Canada, the U.K., Spain and Sweden had expansions that reached 15 years and beyond between the early 1990s and 2008. Without the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the U.S. might have, too.” If trade tensions begin to subside (a big “if”) and if the fruits of deregulation and corporate tax reform kick in, we could see economic growth well into 2020 (and with some luck, into 2021 and beyond). But, let me caution, few have accurately and consistently called economic turning points.

The Fed to the rescue

Rising major market indexes for much of the year can be traced to positive U.S.-China trade headlines (at least through early May), a pivot by the Fed, and general economic growth at home. We witnessed a modest pullback in May after trade negotiations with China hit a snag. The threat of tariffs against Mexico added to the uncertain mood until June 4th, when Fed Chief Jerome Powell signaled the Fed would consider cutting interest rates to counter any negative economic headwinds.

While Powell’s not promising to deliver any rate cuts, one key gauge from the CME Group that measures fed funds probabilities puts odds of a rate cut at the July 31st meeting at 100% (as of June 28 – probabilities subject to change). I’ll keep it simple and spare you the academic theory explaining why lower interest rates are a tailwind for equities. In a nutshell, stocks face less competition from interest-bearing assets.

But let’s add one more wrinkle–economic growth. Falling rates in 2001 and 2008 failed to stem the outflow out of stocks as economic growth faltered. And, rising rates between late 2015 and September 2018 didn’t squash the bull market. During the mid-1980s, mid-1990s, and late 1990s, rate cuts by the Fed, coupled with economic growth, fueled market gains.

It’s not a coincidence that bear markets coincide with recessions and the bulls are inspired by economic expansions. Ultimately, steady economic growth has historically been an important ingredient for stock market gains.

Table 2: Key Index Returns

Source: Wall Street Journal, MSCI.com, Morningstar, MarketWatch, Yahoo Finance

MTD returns: May 31 - Jun 28, 2019

YTD returns: Dec 31, 2018 - Jun 28, 2019

*Annualized

**in US dollars

Final thoughts

Control what you can control. You can’t control the stock market, you can’t control headlines, and timing the market isn’t a realistic tool. But, you can control your portfolio. Your plan should consider your time horizon, risk tolerance, and financial goals. There is always risk when investing, but we tailor our recommendations with your financial goals in mind. If you’re unsure or have questions, let’s have a conversation. That’s what we’re here for.

MTD returns: May 31 - Jun 28, 2019

YTD returns: Dec 31, 2018 - Jun 28, 2019

*Annualized

**in US dollars

Final thoughts

Control what you can control. You can’t control the stock market, you can’t control headlines, and timing the market isn’t a realistic tool. But, you can control your portfolio. Your plan should consider your time horizon, risk tolerance, and financial goals. There is always risk when investing, but we tailor our recommendations with your financial goals in mind. If you’re unsure or have questions, let’s have a conversation. That’s what we’re here for.